How To Find Your Moral Courage

In the early hours of the morning on April 9, 1940, the Nazis invaded Norway.

Sixty-two days later, the government officially surrendered, making Norway the country that withstood a Nazi invasion for the longest period of time (excepting the Soviet Union.)

The Norwegian King and his government fled to London, and a pro-Nazi puppet government was installed in its place, led by Vidkun Quisling, the leader of the country’s existing fascist party and an ardent admirer of Adolf Hitler.

This invasion was a big deal to Hitler, who was obsessed with Norway. He saw Norwegians as the most superior race1, and dreamed of turning the country into an Aryan utopia. The country’s Jewish population and Nazi political opponents were sent to concentration camps, while the new government immediately began implementing Hitler’s plans. They built bridges and roads to connect Germany to Norway. They sketched up plans for opera halls and art museums that would celebrate German culture. They took destroyed Norwegian towns and started rebuilding them to look like German ones. Tens of thousands of German soldiers arrived, not only to enforce the regime, but also to hopefully ‘breed’ with Norwegian women to ‘purify’ the race.

Quisling soon began targeting Norway’s schools, knowing that indoctrinating the youth would be essential to securing their desired future. As part of this effort, he demanded that every teacher join a government-controlled organization, which required pledging their loyalty to the regime, updating their curriculum to only teach approved topics, and advocating pro-Nazi values in their classrooms.

The leaders of the former teachers’ union (which Quisling had previously dissolved) came together, absolutely appalled by this demand and unsure of what to do next. Over the next few weeks, they began to shape a plan of resistance. Each of the country’s teachers would be secretly contacted and invited to protest by signing and mailing a statement to the Department of Education.

“According to what the Leader of the new teachers' organisation has said, membership of this organisation will mean an obligation for me to assist in such education, and also would force me to do other acts which are in conflict with the obligation of my profession. I find that I must declare that I cannot regard myself as a member of the new teachers' organisation.”

On February 20th, 1942, 90% of the country’s teachers mailed in their signed copies of this letter. 10,000 teachers turned out to resist, all of whom knew that they were not just risking their livelihoods, but their lives, too.

This is a powerful example of moral courage, what the political psychologist Kristen Monroe2 defines as the ability to do the right thing, even when it’s difficult. I believe this is the quality that we are most in need of at this moment in history. In this article, I’m going to teach you how to find and use yours, as well as how to help other people do the same.

What is moral courage?

Several years ago, I decided to immerse myself in the philosophy and psychology of courage, prompted by one of the most frequent questions I received from our New Happy community: “How can I be brave?”

My response always felt trite, inadequate, or dismissive, and I hoped there was a treasure buried in the research that could be more useful. I ended up spending a few months delving into every major article on the topic; what I discovered has shaped not only what and how I teach, but also the way I live my own life.

What struck me most was learning that courage is defined by the presence of fear. If you’re not afraid, then you’re not being brave. You think that your fear is a sign that you aren’t able to be courageous, so you desist—in fact, it is the proof of your courage, should you persist.

Morally courageous people are just as afraid as you are.3 Those teachers must have been utterly terrified the morning that they dropped their statements into mailboxes all over the country. They must have looked at their classrooms and wondered if they’d be allowed back. They must have held their children tighter and worried that they might be taken away from them. Yet despite all the risks, something still compelled them to do it.

That something is best captured in a quote from Franklin Delano Roosevelt, cited by Monroe:

“Courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the assessment that something else is more important than fear.”

This is what separates morally courageous people from the rest of us. It’s also what points us towards the work we must do to become more like them: identifying our own “something else”—defining what matters more than our fear.

How to find your something else

Deep within the bowels of a ship, there lies a ballast tank, which is filled with water to serve as a stabilizing force for the ship; it’s especially important when navigating stormy seas, for without its heavy weight, the ship might capsize. Within the body of a human lies our own steadying weight, equally as essential in our own stormy moments—for us, though, the ballast is our core values.

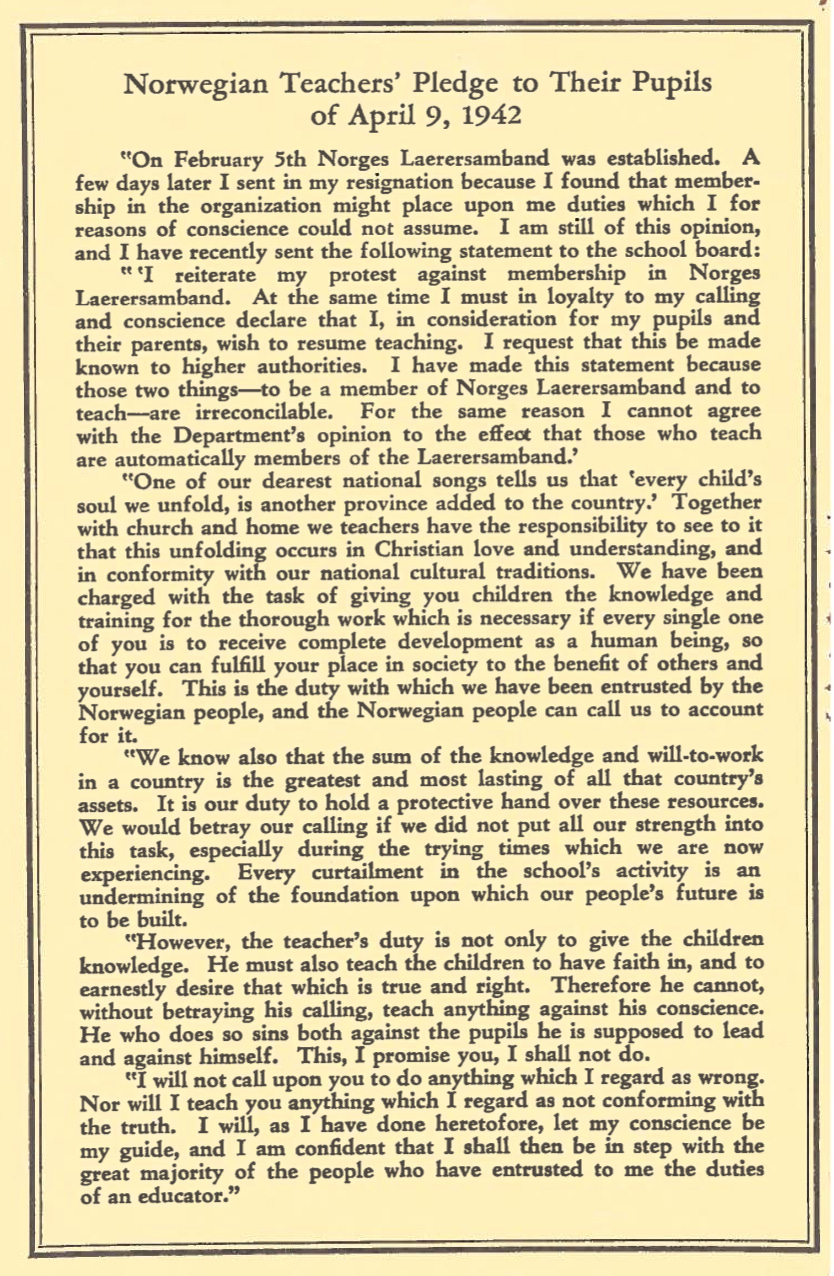

Values like equality, justice, compassion, and fairness are a uniquely powerful force that can help us rise above our fear. They are what motivated Norway’s teachers, as you can see in this public pledge that was released two months after their protest:

The teachers knew what mattered most to them:

Their sacred duty and calling to cultivate the minds of children and help them develop into whole human beings

The need to protect the traditions and culture of their country, as well as the collective progress that was achieved by their ancestors

The desire to honor their own sense of what is sense of right and wrong

The hope of being a protective role model, someone who will never demand a child does something they are not willing to do themselves

The goal of building a better world where every child can live a life that benefits themselves and others

To act with moral courage, you, too, must have an answer to this question: what matters to me more than my fear? Articulate it as clearly as you can. (If you’d like some help, we developed a free tool called the Values Wheel which you can download that will guide you through the process.)

How to live by your values

One of Monroe’s most fascinating findings was that morally courageous people don’t typically start out with momentous acts—they start with small ones. This is what equips them to build what she calls “the moral muscle.”

That was certainly true in Norway. Well before the day that they mailed in their letters, the teachers had begun resisting the Nazi government. They wore pins to honor their state and the royal family, which were quickly deemed illegal. In response, they began wearing a paperclip on their lapels, a symbol of their connection to one another and determination to stand together. Soon, those were banned, too.

These actions were part of a broader pattern of civil disobedience demonstrated by many of the country’s citizens4, from refusing to sit next to Nazis on the bus (which was, of course, soon outlawed) to boycotting German businesses to (ironically) wearing red hats as a symbol of their resistance. Students would refuse to stand up when a government official entered the classroom, and walk out of school assemblies when there were pro-Nazi presentations, all with their teachers’ implicit support.

By the time that Quisling demanded their teachers join the fascist government organization, their moral muscles were ready for the challenge. In the same way, we must prepare ourselves for the challenges in our future by exercising our own morals today.

Decide on one small way you will honor your values today:

If you value justice, you might share a petition with your friends and family.

If you value well-being, you might donate to a GoFundMe that’s helping to support someone’s healthcare bills.

If you value empathy, you might strive to be a more present listener for your loved ones.

At the end of the day, pause and reflect on how you did. It’s important to be willing to look honestly at ourselves and recognize the moments where we fall short on honoring our values. These are often our biggest learning opportunities, for they present us with a chance to evaluate the gap between our intentions and our impact (or lack thereof), and plan for how we’d like to behave differently in the future.

Moral courage doesn’t happen alone

In the days following the teachers’ letter-writing protest, Quisling meted out punishment. He shut down the country’s schools, pretending there was an issue with the heating systems. In response, hordes of angry parents began sending their own letters to the Department of Education (200,000 of them, in fact) complaining that their children weren’t being educated properly and demanding that Quisling bring them back immediately.

The widespread public support for the teachers’ actions made it possible for them to stay strong, even when Quisling escalated his retribution still further, arresting over 1,000 teachers. Again, their fellow citizens came through, organizing donations to pay the captured teachers’ salaries, so that they could remain mentally strong and cease worrying about the impact on their own families.

Eventually, Quisling sent 499 of the arrested teachers to a concentration camp further north. When Norwegians heard this, thousands of them lined up next to the train tracks to sing songs to the passengers and give them food to carry with them. They banded together to protect one another and survive the terrible conditions; tragically, one of the teachers died there.

We don’t just need our values in these scary times; we also deeply need each other. It is by witnessing others act courageously that we are compelled to do the same; it is by having our own courage appreciated that allows us to keep persevering.

The Norwegian resistance masterfully created a community and movement to support the teachers. In a message sent to their king, in exile in London, they described it:

“There is a darkness in Norway today. The Norwegian people are crushed by an iron heel… But a flame has been lit which shines through the darkness: every Norwegian is ready today to play his part in throwing off the yoke of the oppressors. They see that the Norwegian teachers are fighting, despite suffering and anguish, as proud and courageous unarmed shock troops in the battle for the very life of the foundations of the Norwegian people: freedom and culture.

Even if it still feels too scary to speak up yourself, you can still exercise your moral muscle by showing up for those who persist—by celebrating and amplifying their voices, their actions, and their impact.

Make it a rule for yourself: “I will never let a moment of moral courage go unnoticed or uncelebrated.” Remember the symbol of the paperclip and let no one stand alone. Through our communities, we can sustain the individual flames of moral courage and build them into a roaring fire that brings the light back to our world.

A month after sending the teachers north, Quisling realized that he was fighting a losing battle. The community support behind their cause was too strong. By November of that year, the surviving teachers had returned to their schools, which would remain free of Nazi ideology, thanks to their moral courage.

Send this newsletter to someone who wants to be brave. Thanks for being a part of the New Happy movement to build a happier world. Learn more here.

This gave many Norwegians a tremendous level of protection that they could use to protest and advocate for others. It’s a critical lesson for those of us who have privilege here and now: what are we doing with it?

Whose insights have been instrumental to the development of the New Happy philosophy, and whose entire body of work I highly recommend.

When we deny the presence of fear in other people who are behaving courageously, it also becomes easier to abdicate our responsibility to do the same. We can look at people and say things like, ‘They’re just braver than me; I could never do that.’

It was, of course, not the entire population: there were Nazi collaborators within Norway, like in all other occupied countries.

This is a fabulous story for moral formation! Slow work, done in community with spirit amid fear. Thank you.

Thanks for a great read!

This makes me proud to be Norwegian. If something similar happened today, I'm not totally sure if we could do this again, but the teachers are one of the groups with the best moral integrity.

And now even the most right-wing finance people here says that whats going on in the US is crazy, so it is hope that we don't slide into the abyss.